- ensure that children have the benefit of both parents’ involvement in their lives to the extent that this is consistent with the their best interests;

- protect children from physical or psychological harm

- protect children from being subjected, or exposed, to family violence, child abuse or neglect;

- ensure that children receive adequate parenting so that they may achieve their potential; and

- ensure that parents fulfil their parental duties relating to a child’s care, welfare and development

The principles underlying the stated purposes of Pt VII are that:

- children have a right to know and be cared for by both parents, regardless of their relationship status;

- children have a right to spend time and communicate with both their parents and other people who have an important role in their lives;

- parents should share responsibilities concerning the care, welfare and development of their children;

- parents should strive to agree about the future parenting of their children; and

- children have a right to enjoy their culture and the company of those who partake in their culture.

Another fundamental aspect of the Family Law Act’s parenting regime is the concept of “parental responsibility.” “Parental responsibility” means “all the duties, powers, responsibilities and authority which, by law, parents have in relation to their children.” Parents have parental responsibility in relation to their children, subject to an order of the court re-allocating those responsibilities.

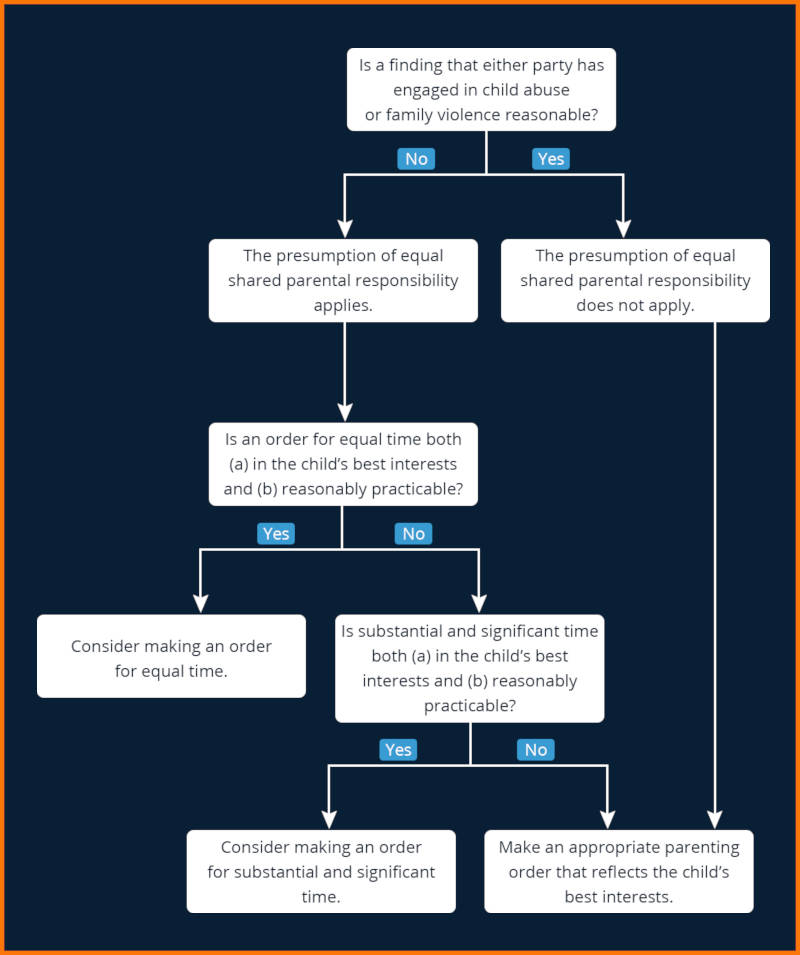

Section 61DA(1) of the Family Law Act provides that, when making a parenting order, the court must apply a presumption of equal shared parental responsibility. This presumption will not apply when there are reasonable grounds to believe that a parent, or a person who lives with a parent, has:

- committed family violence; or

- abused the child or another child who, at the time, was a member of that person’s family.

Moreover, the presumption may be rebutted where there is evidence satisfying the court that an order for equal shared parental responsibility would not be in the child’s best interests. The court may also consider the presumption of equal shared parental responsibility inappropriate in interim proceedings. This might occur where there are allegations of family violence and the court is unable to determine the matter given the state of available evidence.

Parenting Orders

A parenting order is an order under the Family Law Act that deals with any of the following matters:

- the person with whom a child is to live;

- the time that the child is to spend with a person;

- the allocation of parental responsibility in relation to the child;

- provision for communication between another person and the child;

- the form of consultations that persons with parental responsibility in relation to the child are to have with one another;

- the steps that should be taken before an application to a court is made to vary an existing order;

- The process to be relied upon for resolving disputes about the terms or operation of the order; and

- Any matter concerning the care, welfare and development of the child.

Who Can Apply for Parenting Orders?

The class of persons who can apply for parenting orders is broad. Section 65C of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) provides that the following individuals may apply for parenting orders:

- either of the child’s parents;

- the child;

- either of the child’s grandparents; or

- any person concerned with either the care, welfare or development of the child.

Whether a person is concerned with the care, welfare or development of a child is a question of fact to be determined in the circumstances of a given case.

Section 65C should not be interpreted so as to create a hierarchy of applicants. For example, the fact that “parent” appears before “grandparent” in the list of people who may apply for parenting orders does not signify that parents should be given greater priority than grandparents.

Shared Parental Responsibility

Section 65DAC(2) of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) states that an order for shared parental responsibility requires that decisions concerning major long-term issues affecting a child be made jointly. It is unclear, however, whether this imposes an obligation upon the parties to jointly decide such issues. For instance, if the parties are genuinely at odds with one another in respect of a major long-term issue, it would seem manifestly unjust to conclude that both parties have contravened the order. Additionally, there is no evidence in the Explanatory Memorandum to the Family Law Act suggesting that s 65DAC(2) creates a binding obligation. It may very well be the case that it is meant to promote a more co-operative approach to parenting, rather than a legally enforceable duty.

Section 65DAC(3),on the other hand, requires the parties to genuinely consult with one another in relation to any major long-term issues affecting the child. Accordingly, a failure to consult with the other party in relation to a major long term issue may amount to contravening the order.

An order for shared parental responsibility does not require third parties to establish that a decision concerning a major long-term issue is a joint decision. For instance, a doctor who provides medical treatment to a child need not establish that the relevant individuals jointly decided that the child should receive medical treatment. Nor do orders for parental responsibility require that the parties consult one another in relation to day-to-day issues affecting the child. Day-to-day issues include matters such as the child’s bedtime, what T.V. programs they are allowed to watch, what types of meals they should eat, etc.

The Best Interests Principle

Whenever the court makes a parenting order, it must regard the child’s best interests as the paramount consideration. This is the paramountcy principle.

Section 60CC of the Family Law Act sets out two categories of consideration that the court must take into account in determining the child’s best interests. The distinction between primary and additional considerations both underscore the greater significance ordinarily accorded to the primary considerations and focuses the court’s inquiry on the revised objects of the Family Law Act’s parenting regime.

The primary considerations are:

- the benefit to the child of having a meaningful relationship with both of the child’s parents; and

- the need to protect the child from physical or psychological harm resulting from being subjected, or exposed, to abuse, neglect or family violence.

Circumstances may arise where the primary considerations conflict. For example, a finding of child abuse may support the inference that a child could be at risk harm if they were to spend time with a one of their parents. Where the primary considerations conflict, the court must resolve the conflict in favour of protecting the child.

The additional considerations are comprised of the 13 matters set out in s 60CC(3) of the Act:

- any views expressed by the child and any factors (such as the child’s maturity or level of understanding) that the court thinks are relevant to the weight it should give to the child’s views;

- the nature of the relationship of the child with:

- each of the child’s parents; and

- other persons (including any grandparent or other relative of the child);

- the extent to which each of the child’s parents has taken, or failed to take, the opportunity:

- to participate in making decisions about major long-term issues in relation to the child; and

- to spend time with the child; and

- to communicate with the child;

- the extent to which each of the child’s parents has fulfilled, or failed to fulfil, the parent’s obligations to maintain the child;

- the likely effect of any changes in the child’s circumstances, including the likely effect on the child of any separation from:

- either of his or her parents; or

- any other child, or other person (including any grandparent or other relative of the child), with whom he or she has been living;

- the practical difficulty and expense of a child spending time with and communicating with a parent and whether that difficulty or expense will substantially affect the child’s right to maintain personal relations and direct contact with both parents on a regular basis;

- the capacity of:

- each of the child’s parents; and

- any other person (including any grandparent or other relative of the child); to provide for the needs of the child, including emotional and intellectual needs;

- the maturity, sex, lifestyle and background (including lifestyle, culture and traditions) of the child and of either of the child’s parents, and any other characteristics of the child that the court thinks are relevant;

- if the child is an Aboriginal child or a Torres Strait Islander child:

- the child’s right to enjoy his or her Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander culture (including the right to enjoy that culture with other people who share that culture); and

- the likely impact any proposed parenting order under this Part will have on that right;

- the attitude to the child, and to the responsibilities of parenthood, demonstrated by each of the child’s parents;

- any family violence involving the child or a member of the child’s family;

- if a family violence order applies, or has applied, to the child or a member of the child’s family–any relevant inferences that can be drawn from the order, taking into account the following:

- the nature of the order;

- the circumstances in which the order was made;

- any evidence admitted in proceedings for the order;

- any findings made by the court in, or in proceedings for, the order;

- any other relevant matter;

- whether it would be preferable to make the order that would be least likely to lead to the institution of further proceedings in relation to the child; and

- any other fact or circumstance that the court thinks is relevant.

These considerations do not form part of a hierarchy whereby some considerations are regarded as more important than others. The weight accorded to any particular consideration depends on the facts and circumstances of the case at hand. Accordingly, it is possible for a secondary consideration to carry more weight than a primary consideration in a particular case.

How Courts Resolve Parenting Disputes

Goode & Goode [2006] FamCA 1346 is the first decision of the Full Court of the Family Court of Australia to examine the relationship between the presumption of equal shared parental responsibility and the child’s best interests in light of the 2006 amendments to the Family Law Act. To that end, the Full Court described the decision making process that judicial officers should undertake in resolving family law disputes. That process is outlined below.

“Equal time” refers to an arrangements whereby the relevant parties spend time with a child in equal proportions. A child may living with each parent on a week-about basis would be an example of an equal time arrangement.

“Substantial and significant time” is time that a child spends with a parent which must include days that fall on:

- weekends;

- holidays;

- non-weekends; and

- non-holidays.

Moreover, substantial and significant time must allow the relevant parent to be involved in:

- the child’s daily routine; and

- occasions and events that are significant to either the child or parent.

The court is required to have regard to the following factors in determining whether the time that a parent spends with a child is “reasonably practicable” :

- the distance between the parties’ households;

- the parties’ ability to implement arrangements for equal time or substantial and significant time;

- the parties’ capacity to resolve issues that might arise concerning contact arrangements;

- how the proposed custody arrangements might affect the child; and

- any other matters the court considers relevant.

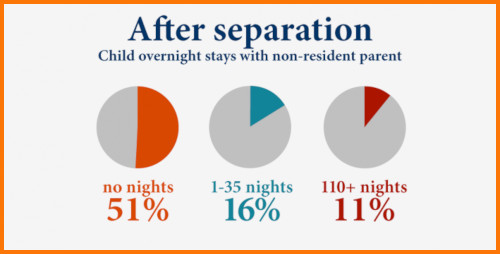

Substitute “Number of overnight visits a child has with non-custodial parent after separation” for “After separation: Child overnight stays with non-resident parent.”

Varying and Terminating Parenting Orders

Under s 65D(2) of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth), the court has the power to discharge, vary , or suspend either a parenting order or any part of a parenting order. The Act does not, however, set out any specific grounds for varying a parenting order. Nonetheless, courts are generally reluctant to vary parenting orders because of the detrimental effect that repeated litigation may have on children.

The leading case on the issue of whether a parenting order should be varied is the Full Court decision of Rice v Asplund. Rice v Asplund is authority for the proposition that in applying to have a parenting order varied, the applicant bears the onus of demonstrating a change in circumstances sufficient to justify a hearing.

Parenting orders may also be terminated. Termination of a parenting order will occur upon:

- the child reaching 18 years of age;

- the child marrying under the age of 18;

- the child entering into a de facto relationship under the age of 18;

- the child’s adoption; or

- the child’s death.

Independent Children's Lawyer

Independent children’s lawyers are appointed under a court order to represent a child’s interests. Such orders can be made on the court’s own initiative. Alternatively, they can be sought by either the child, an organization concerned with the child’s welfare or any other person.

It is important to bear in mind that independent children’s lawyers represent the child’s interests – not the child. Accordingly, they are not required to act on the child’s instructions. Their role is to form a view of the child’s interests so that it may be conveyed to the court.

The Full Court of the Family Court enumerated a set of considerations to be taken into account in deciding whether the child’s best interests might require appointing an independent children’s lawyer. They consist in:

- allegations of child abuse, including physical, psychological or sexual;

- the presence of an apparently intractable conflict between the parties;

- alienation of the child from either or both parents;

- religious or cultural issues affecting the child;

- significant medical, psychological or psychiatric conditions in relation to the parties, the child or any other person having significant contact with the child;

- the presence of material suggesting that it may be inappropriate for the child to live with either parent;

- the sexual preferences of any person having significant contact with the child and how it might seriously affect the child’s welfare;

- cases where the child is of mature age and expresses strong, thoughtful views concerning custodial arrangements;

- any proposal of either party to remove the child from Australia;

- cases involving the separation of siblings;

- cases concerning custodial arrangements where neither party is legally represented;

- certain cases involving the court’s welfare jurisdiction: Re: K (1994) FLC 92-461

The process whereby the report is prepared generally involves an interview with the child’s parents, the child and any other members of the relevant households. In addition to the interview, the family consultant may observe how the child interacts with each of the interviewed parties.

Family Reports

International Child Abduction

A person with “rights of custody” in relation to a child may apply to the relevant Central Authority in Australia when the child has been wrongfully removed to another Hague Convention Country. A child is wrongfully removed from Australia if:

The child is has not attained the age of 16 years;

The child “habitually resided” in a Hague Convention Country before their removal from Australia;

The person seeking to return he child has “rights of custody” under the law of the relevant Hague Convention country; and

The removal breaches the “rights of custody”.

An application must be filed within 1 year from the day that the child was either removed or retained. There are, however, circumstances where the child’s return may be refused:

The applicant was not “exercising rights of custody” at the time of the wrongful retention or removal;

The applicant either consented or acquiesced to the child’s removal or retention;

There is a grave risk of either physical or psychological harm to the child;

The child objects to their return;

Returning the child is not permitted in view of the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms; or

The child is settled in their new environment.